Blame RitaPita

Not really!

Not really!But her "tag" for all things book related made me take a good look at the books I have on my shelf. I felt bad for leaving some of them out in the last post, so I wanted to showcase them in some way. All of the books below are highly recommended.

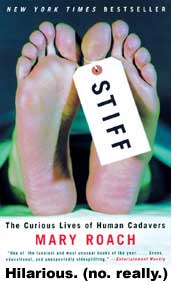

Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach

I know this sounds awful, but this is one of the funniest books I've ever read. You're going to find yourself rolling on the floor laughing while tackling topics like dissection, crucifixion and cannibalism. Yes, I am a freak. So are you. Buy it.

Here's an excerpt: (This sort of thing is probably illegal, but I'm just trying to sell more books for ya, Mary baby.)

The human head is of the same approximate size and weight as a roaster chicken. I have never before had occasion to make the comparison, for never before today have I seen a head in a roasting pan. But here are forty of them, one per pan, resting face-up on what looks to be a small pet-food bowl. The heads are for plastic surgeons, two per head, to practice on. I'm observing a facial anatomy and face-lift refresher course, sponsored by a southern university medical center and led by a half-dozen of America's most sought-after face-lifters.(see how easy it is to blog when you simply rip use the excellent work of someone else?)The heads have been put in roasting pans - which are of the disposable aluminum variety - for the same reason chickens are put in roasting pans: to catch the drippings. Surgery, even surgery upon the dead, is a tidy, orderly affair. Forty folding utility tables have been draped in lavender plastic cloths, and a roasting pan is centered on each. Skin hooks and retractors are set out with the pleasing precision of restaurant cutlery. The whole thing has the look of a catered reception. I mention to the young woman whose job it was to set up the seminar this morning that the lavender gives the room a cheery sort of Easter-party feeling. Her name is Theresa. She replies that lavender was chosen because it's a soothing color.

It surprises me to hear that men and women who spend their days pruning eyelids and vacuuming fat would require anything in the way of soothing, but severed heads can be upsetting even to professionals. Especially fresh ones ("fresh" here meaning unembalmed). The forty heads are from people who have died in the past few days and, as such, still look very much the way they looked while those people were alive. (Embalming hardens tissues, making the structures less pliable and the surgery experience less reflective of an actual operation.)

For the moment, you can't see the faces. They've been draped with white cloths, pending the arrival of the surgeons. When you first enter the room, you see only the tops of the heads, which are shaved down to stubble. You could be looking at rows of old men reclining in barber chairs with hot towels on their faces. The situation only starts to become dire when you make your way down the rows. Now you see stumps, and the stumps are not covered. They are bloody and rough. I was picturing something cleanly sliced, like the edge of a deli ham. I look at the heads, and then I look at the lavender tablecloths. Horrify me, soothe me, horrify me.

They are also very short, these stumps. If it were my job to cut the heads off bodies, I would leave the neck and cap the gore somehow. These heads appear to have been lopped off just below the chin, as though the cadaver had been wearing a turtleneck and the decapitator hadn't wished to damage the fabric. I find myself wondering whose handiwork this is.

"Theresa?" She is distributing dissection guides to the tables, humming quietly as she works.

"Mm?"

"Who cuts off the heads?"

Theresa answers that the heads are sawed off in the room across the hall, by a woman named Yvonne. I wonder out loud whether this particular aspect of Yvonne's job bothers her. Likewise Theresa. It was Theresa who brought the heads in and set them up on their little stands. I ask her about this.

"What I do is, I think of them as wax."

Theresa is practicing a time-honored coping method: objectification. For those who must deal with human corpses regularly, it is easier (and, I suppose, more accurate) to think of them as objects, not people. For most physicians, objectification is mastered their first year of medical school, in the gross anatomy lab, or "gross lab," as it is casually and somewhat aptly known. To help depersonalize the human form that students will be expected to sink knives into and eviscerate, anatomy lab personnel often swathe the cadavers in gauze and encourage students to unwrap as they go, part by part.

The problem with cadavers is that they look so much like people. It's the reason most of us prefer a pork chop to a slice of whole suckling pig. It's the reason we say "pork" and "beef" instead of "pig" and "cow." Dissection and surgical instruction, like meat-eating, require a carefully maintained set of illusions and denial. Physicians and anatomy students must learn to think of cadavers as wholly unrelated to the people they once were. "Dissection," writes historian Ruth Richardson in Death, Dissection, and the Destitute, "requires in its practitioners the effective suspension or suppression of many normal physical and emotional responses to the wilful mutilation of the body of another human being."

Heads - or more to the point, faces - are especially unsettling. At the University of California, San Francisco, in whose medical school anatomy lab I would soon spend an afternoon, the head and hands are often left wrapped until their dissection comes up on the syllabus. "So it's not so intense," one student would later tell me. "Because that's what you see of a person."

The surgeons are beginning to gather in the hallway outside the lab, filling out paperwork and chatting volubly. I go out to watch them. Or to not watch the heads, I'm not sure which. No one pays much attention to me, except for a small, dark-haired woman, who stands off to the side, staring at me. She doesn't look as if she wants to be my friend. I decide to think of her as wax. I talk with the surgeons, most of whom seem to think I'm part of the setup staff. A man with a shrubbery of white chest hair in the V-neck of his surgical scrubs says to me: "Were y'in there injectin' 'em with water?" A Texas accent makes taffy of his syllables. "Plumpin' 'em up?" Many of today's heads have been around a few days and have, like any refrigerated meat, begun to dry out. Injections of saline, he explains, are used to freshen them.

Abruptly, the hard-eyed wax woman is at my side, demanding to know who I am. I explain that the surgeon in charge of the symposium invited me to observe. This is not an entirely truthful rendering of the events. An entirely rendering of the events would employ words such as "wheedle," "plead," and "attempted bribe."

"Does publications know you're here? If you're not cleared through the publications office, you'll have to leave." She strides into her office and dials the phone, staring at me while she talks, like security guards in bad action movies just before Steven Seagal clubs them on the head from behind.

One of the seminar organizers joins me. "Is Yvonne giving you a hard time?"

Yvonne! My nemisis is none other than the cadaver beheader. As it turns out, she is also the lab manager, the person responsible when things go wrong, such as writers fainting and/or getting sick to their stomach and then going home and writing books that refer to anatomy lab managers as beheaders. Yvonne is off the phone now. She has come over to outline her misgivings. The seminar organizer reassures her. My end of the conversation takes places entirely in my head and consists of a single repeated line. You cut off heads. You cut off heads. you cut off heads.

Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris

If you don't know David Sedaris, a frequent contributor to NPR and PRI radio programs, please pick up one of his books. This is my personal favorite, yet not his most recent release. The stories revolve around his life and the lives of his family members. In a really twisted, warped, hilarious way.

Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth by Chris Ware

I always enjoyed graphic novels. Not so much comic books - I was never one of those kids that hoarded old issues of Fantastic four while reading by candlelight in the attic. (Anyway, we didn't have an attic.) Graphic novels were always a bit more adult - but the popular ones usually stuck to the fantasy/sci-fi range.

Chris Ware went ten steps further. If you think that you can't be as affected emotionally by a book with pictures as you can by any other novel, I suggest you give Ware a try. The storytelling is well up to par with the incredible art in this tone, and the six years he put into creating this work were well worth it.

A few others:

A Million Little Pieces by James Frey

An excellent telling of one man's journey from addiction to recovery that pulls no punches.

Rush Limbaugh is a Big Fat Idiot by Al Franken

I don't care how much weight he lost, this book is still freakin hilarious. Pop some oxycontin, settle down with a glass of wine (not made in France) and enjoy.

Madam Secretary: A Memoir by Madeleine Albright

I started reading this on a very long train trip and was finished by the time I arrived. It's not a quick read (it was a VERY long train trip), but it's a fascinating story of Albright's life journey from adopted child to first female Secretary of State for the United States of America.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home